Looking For Water

Text: Tim MacGabhannPhotographs: Keith Dannemiller

0: Vertigo

I used to spend days off on my rooftop, drifting between reading and sleep, heat-dreams rewriting the words I’d read until I could no longer tell where sentence tapered into dream. For me, reading and dreaming are the same walk over thin paths worn into dark earth and blanketed ash, a forest of black trees all around. In my dreams a sea-roar is audible always in the middle distance: when I’m awake, it’s the noise of traffic and flight paths. I never used to care until I jerked awake and had to double back along the wrong turn to where the two paths canceled, trees becoming paths again, the perpendicular axes flipping back into place.

I’ve been spared that rooftop vertigo lately. Mexico City’s air has been white with smog since mid-March: go outside for too long and you’ll get an itch at your glottis no amount of water can drown, airborne dirt will lend your glasses a sepia filter, the ozone will sting your nose until it bleeds. Our half-collapsed sewage pipes often burst, and these spills dry and turn to dust and rise into the air. This is why when the poorer areas like Iztapalapa and Tlahuac get flooded by rainy season, alerts go round about nineteenth-century diseases: typhoid, cholera. Inferno, Circle 3: a fine shit drizzle forever.

The city government measures air pollution in ‘imecas’ — Indice Metropolitana de Contamination del Aire, ‘Metropolitan Index of Air Pollution’, a parts-per-million measure of carbon monoxide, ozone, and other harmful sulphides. To my ear that acronym sounds like a made-up indigenous people, named after their tiny white poison arrows, an invented fame that’s preserved in the all-angled, flurrying particle blizzard we walk into when we leave our houses.

A measure of 50 imecas on the government site means the air is safe to breathe. Levels currently tip 150. Even deep into the summer months’ rainy season, we might well exceed the 1986 record of 450 imecas. As it stands, the current level is a fourteen-year high, one that makes our skies look like cotton wadded into a bell-jar.

The city government updates its site daily, posting a map dotted with coloured discs that indicates air quality in each of the city’s 16 delegaciónes. Green dots indicate clean air, but our maps these days are rashed with dull greys and yellows. I look at that map every night—earlier and earlier, it feels like, since the carbon monoxide makes sleep drop faster and heavier than usual, thick and powdery and merciful, at 10.30, 10, even 9.30—and you can’t help it, you feel like it’s that Don Paterson sonnet about the end of the world:

“I watched a download bar And drank the last thing in the house. […] One by one we fell asleep And that is how they found us all.”

1: Hoy No Circulo

I was at Andrew Birk’s gallery closing on Saturday. The toilets and sinks ran out of water before the drinks ran out. Too many of us in too small a space: Mexico City in miniature.

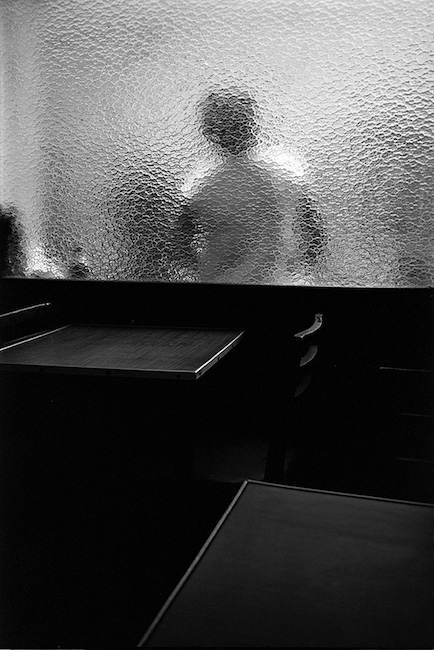

There was a DJ, pilled-up dancers. The party would last past all thirst. I went looking for water before they could, found some, stood on the metal fire-exit and the shapes below were like a Bach fugue. I quit booze and drugs eighteen months ago but claustrophobia gives me the same trapped-in-an-underground-carpark vibe as hydroponic weed once did. So does reading bad news. The worst yet had broken that week, Yale scientists reporting that ice content in clouds had been referring to cold water all along, meaning all the projections have to be revised, shortened.

The tight press, the bad air, the worse news, the sweat: I was getting that petrol-scented yellow smog-weight at the front of my skull, the one that presages migraine.

An environmentalist I know says “Cities don’t cause heatwaves: they just turn them into disasters.” She is right: Mexico in April is not supposed to be 26 degrees, and certainly not at 6pm. I thought of what she’d told me about the summer 2003 heatwave — the one that killed 70,000 Europeans across 12 countries, more than any conflict since World War II, and 35 times worse than Hurricane Katrina, 70 times worse than SARS or swine flu.

I tried to not want to smoke. On my phone the temperature difference between Mexico City and rural Tepoztlán—my favorite getaway spot—was about ten degrees. Except, of course, Tepoztlán also had a forest fire to deal with: another heatwave.

I sipped water and chewed nicotine gum and tried to decide if the evening sky looked more like an octopus or a manta ray. The livid wedge shape, the low, hungering loom of the blood-colored shape: yeah, definite manta-ray. But it could also be an octopus beak, and the lit smoke-plumes from the refinery could be tentacles.

The sky was a platinum shimmer: metal particles in combustion, a broken sheet of dazzle. Silver leaves came spinning down from the eucalyptus trees: the worst plant you can have in this city. They’re greedy for water, sucking up whatever droplet is left in the swamp the Spanish drained after conquering the Aztecs. Python roots that ruck pavements, burst pipes, bleed us of moisture. All major cities have a body of water within them, but all of this city’s rivers diverted underground to make way for the major eje highways. The city’s vast thirst has sucked down most of these aquifers, and now it’s starting on the volcanic springs of poor towns in the southwest. The battle for water has already started in villages like San Bartolo Ameyaco, with residents fighting off the police sent to secure water supplies for the city government.

On the floor of the gallery Andrew had strewn bougainvillea petals, little lung-shapes, dried-out, pulverized by dancing feet. I didn’t like the music. I am on a late Bowie jag in my listening these days, partly because he died but also because the hot clean shine of the production rhymes in my head with the oppressive, temperature-boosting glare the sun throws back off the skyscrapers and tarmac here. Breathing in through my nose gave me an ammoniac tang: I thought of the city’s gut-shape on the map, our soured air an acidoketosis from a gut stuffed on 24 million commuters, their aircon, petrol, cigarettes, labour, their 15kg-per-person of solid waste per day, their 6 million cars, 10% of which are so old—the average age of vehicles in Mexico is 17—that they shouldn’t be on the road.

After a while I gave up on the non-smoking thing and went into the office to rob a cigarette off of the gallery owner. It wasn’t a gratuitous, may-as-well thing: it was because I needed some nicotine to quicken the blood, something to speed me through the thickening smog in my head so I could get back home in a lucid state before the migraine storm really started. I texted the girl I am seeing, O., to cancel a date. Don’t worry, she said. I can’t really breathe if I go outside. She has bad allergies. O. added a joke: Hoy no circulo. “Today I don’t circulate”: a pun on the car bans the government has had in place since mid-March to keep the traffic down by a sixth. Hoy No Circula says the notice posted on the site, and it’s cars ending in a one on a Monday, say, or a two on Tuesday, or whatever. The joke about circles put me in Dante’s circles again, via an association with the Circuito Interior—Interior Circuit—highway I’d taken to get to Andrew’s from my place: that peristalsis of traffic, the other roads veering in and out all around, an intestinal coil.

The horizon was a great white scar. A flare glided over: widening jet contrails the color of blood. I couldn’t look anymore, so I looked down at the dancers, their idiot trance, how they faced the DJ, the music. How they danced.

Vigny and Baudelaire, de l’Isle d’Adam and early Mallarmé, they did gnostic riffs on Dante’s circles to talk about the modern city, the shut-in industrial sky appearing to them as the ceiling of a Manichean universe, Satan refigured as a laboratory demiurge experimenting on humanity: ‘the low, heavy sky weighs like a lid’, says Baudelaire, the best one. But for those poètes maudits—‘damned poets’: their emo name, not mine—the smog age’s first blood suns were the Book of Revelation’s red sun, that time in history when adoration of progress turns to a hubris so vertiginous that we mistake our own burning for a glory dazzle. Rev. 18.18: And they did cry when they saw the smoke of her burning, saying, “What city is like unto this great city!” A time in history when Babylon rhymed with Babel, the two destructions rhyming to conclude the one big dialectic of combustion that was human history.

2: Nowhere Man

Heat smother. The imeca count exceeds 150. By deciding to build here, Mexico sealed its own fate. The city is held in a bowl of mountains 7,350 feet above sea level, so the constant stream of high-pressure winds sucks pollution from the industrial centers of Veracruz, Puebla, and Estado de México in on top of us. Bad air kills 2,000 chilangos per year. A post-mortem study of 21 young people’s hearts at a university here found that so much contamination activates genetic problems and latent bacteria: Daniel Hernández’s ontology in negative.

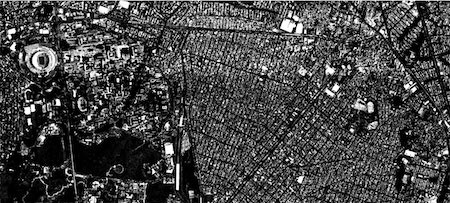

Even holed up in my room, away from the white air, the carbon monoxide levels turn me narcoleptic. Clots in my throat, migraine afternoons where even the glare of pages is too harsh. Forget screens. I lose work. I daydream of myself up to my knees in a yellow sea churn, bowing towards the waves and foam, sleet stinging down, electrical storm’s crackle and boom all around. Full-body shivers, three days of immobility. I lose work, barely eat, half-dream my way through the hot, dim hours. Dates flurry behind my eyes, ash and snow: the 1519 sacking of Tenochtitlán, the Great Flood of 1629, the litany of plagues and floods that dot this city’s history until the earthquakes of 1958 and 1986: Mexico City has survived everything history and nature have thrown so far. Maybe it won’t survive itself. A video went around on social networks last year depicting the city’s spread. From the 1930s’ ‘big village’ of 1.5 million people you can watch the map’s limits creep, roads feeding on outlying villages throughout the ‘50s—Coyoacán, San Ángel Inn, Tres Marías, La Marquésa—until by the mid-‘80s the city fattens like a tumour—Santa Fé, Ciudad Nezahualcoyotl, Iztapalapa—to gobble in dry emptiness, repurposed chemical dumps, rebar-shack suburbs. The city has quadrupled in size since 1980. Everybody has to breathe, piss, shit, work, burn fuel for food and electricity, has to hawk their labour, has to eat: where better to try this than in a place where 24 million people are already doing so? And so the desperate exodus continues from all over the country, the flight from violence, grinding poverty, the poisons of other skies.

On the fourth day, I can stand, wobble about, and arrange to meet my friend Hassan, a Syrian guy who pitched up here after detours through Turkey, Lebanon and Rome. We look alike: beard, unruly hair, indoor pallor. I drive south, detouring through colonial neighbourhoods: Tlalpan, San Ángel, Coyoacán. Cobblestoned streets, houses whose deep-pored stone breathes a deep green cool. O. sends me a short film she’s acted in. Doctor she went to says she has sick building syndrome. The chemicals in aircon buffets, the germ-cyclones above bathroom hand-dryers, the chemical film that dries on top of the skin cells left on desks: all that, it messes her up badly. In the red-lit shapes of the morning clouds I picture her alveoles’ livid pods. “The doctor visit fucked me up,” she texts. “There’s no such thing as clean, turns out, and people aren’t people, but blizzards of disease flakes. Kidnap me to the beach already. You’re the freelancer.” She sends links to songs, photos of her at the desk, bikini shots. I do much the same. Want and dopamine hits drip-fed through a smartphone.

The horizon was a great white scar.

A flare glided over: widening jet contrails the color of blood.

The water I buy at the 7/11 is tepid. I see condensation on the plastic-packaged sandwiches. The air smells of cheese going sour. I try to be grateful: when I’m 60, chugging down tepid 7/11 water probably won’t even be possible. Migraine nausea has me seeing endings and parallels everywhere: that illness solipsism. The city sits on a jelly layer from the drainage of the lake it started out out as. Downtown’s high-rise bulk rests on lakebed silt and volcanic ash, above pipes that roil with tides of sewage, waste, fishbones, shucked-off prawn shells, human slurry, a big dyspeptic stomach like the city’s own map. I will show you fear in a badly-refrigerated convenience store. I’m not sure if I’m exaggerating because I’m messed up or if that messed-up-ness has me tuned into a deeper truth frequency.

Hassan and I have arranged to meet at the UNAM campus. I park, walk across the concourse through a park of dry grasses, nopal, agave, gravel like a desert cemetery in the future. The air isn’t better here, not exactly, but it is less bad — and blue, for a change. I can see all the way to the city’s rim of dormant volcanos. I’m almost able to convince myself I’m looking at the ‘70s Kodachrome tints of my grandfather’s old encyclopedia photos of Mexico City, the ones that lured me here. That colour blue stayed at the back of my mind, gathering associations, until a breakdown caused by burnout and substance abuse brought me here. My rooftop used to be my brighter region, with only TV aerials, blue air, crashing traffic-noise all around. I liked the ritual of tuning out car-static and zeroing in on my head’s signals, watching my attention refine itself to an inanimate, mineral serenity of a receiving antenna.

The café is at the bottom of a gallery. An aesthetic of bare metal, cement benches calcite-mottled with shapes like fossils. Ferns press the glass. Grass sprouts from between black chunks of pedregal volcano scree. This far down, the air-conditioning motor’s long, slow pulsing becomes the heartbeat of Cuicuilco, the Olmec city whose ruins are held inside Mexico City. The Xitle volcano erupted in or around the first or second century AD, swamping the Olmecs in a sulphur-coloured sea of lava. Almost no archaeological trace remains: just a stub of some circular pyramids south of the city. But the lava dried to a layer of blood- and cinder-coloured rock from which the Mexica, Aztecs and Spanish quarried their building materials. Ruin, construction, ruin: again, history as a dialectic of combustion, smoke cursive written on air.

Hassan’s in no mood for my riffs. He’s just gotten his student visa: he radiates dazed relief, like a shipwreck victim washed up safely, his stride loose, unencumbered. “No more of the ‘r’-word,” he says, with a low, warning look at me. Refugee is a term he hates. “The visa says student. That’s what I’m here to be.” He’s not elated by the visa: he doesn’t really do elated. He has a Zen serenity, a strong poker face, a deep-buried, magmatic core of anger. He’s frustrated by the kids at the university in Aguascalientes—a small, car-producing town four hours north of Mexico City—where he’s studying Spanish.

“They’re all Americans,” he says, and tuts. “They just don’t have the passport. You speak to them in Spanish, they answer in English.” His Spanish is pretty good: lack of confidence has him murmuring, but the sharp edge his native Arabic lends to ‘r’-sounds gives him a serrated accent that fits his demeanour. “I like the quiet, though. There isn’t even any weather. The campus looks like a snooker-table: smooth, green. There’s nothing — it’s like a photo of a prospectus.” It is a good fit for him: he’s too quiet, too laconic to fit in with his classmates’ vibe of earnest preppiness. He can be his abstract, calm self.

He agrees. “Yeah, I way prefer Aguascalientes to here: you’re crazy for living here. I’m already exhausted. I mean…the speed of everything? The amount of information coming at you. The smog, the activity. It’s tiring: you have to filter all the facts out of everything you see. What’s valuable, what’s not. It’s like all of the Internet being fired through your head. That’s exhausting.” He sits back in his chair. “But I like how it might all end tomorrow. That’s like Syria. You have a nice attentiveness to things when an earthquake might arrive any moment. You’re utterly absorbed in what you’re doing, because it might be the last thing you do. And, OK, so it might be entirely ordinary, but it could be the last thing ever. And that makes you calmer, maybe, but not like a cow. You’re absorbed, but you’re ready to jump and run any moment. That’s a perfect way to be, in some ways. For a short period, anyway.”

“I don’t know, I like it,” I say, pretending my bad week hasn’t happened. “Coming here as a foreigner makes you part of a bigger story. The Mexica got kicked out of the north and made a home here. Then you have the Republicans after the Spanish Civil War, the Jews before World War II, the first wave of Syrians and Lebanese in the ‘50s, the Uruguayans and Argentines and Chileans during Plan Condor. It’s like the capital of exile.”

Hassan shakes his head, lower lip creased downwards. “Nah. ‘Exile’ means you’re placeless forever. There’s no capital for a state of mind. Leave home, and the word ‘home’ stops meaning anything.”

“What about this thing?” I pick up his phone. “It’s a kind of portable home. I have three continents’ worth of friends on mine. So do you.” I’m thinking of my own nights huddled in over that clamshell glow like a carry-hearth, the afternoons my Dad and I spend texting each other during the choppy live-streams of Liverpool games.

“Facebook’s a game for you. For me it’s the magical tool that changed my life,” he jokes, mimicking the voice of a TV ad. “Our revolution happened online. Bouazizi burned himself in Tunisia, and the TVs tried to keep it quiet — but there was no containing the videos. Like, Share, Send is faster than any state censor. It was the same for the protests and videos of repressions.”

“Was it not all Twitter?”

“No: Twitter is too easy to shut down. With Facebook, you just get spyware blockers and change your password when you log in. It’s tedious, but our police couldn’t break through. You really should do this here. The Internet was like a torrent of information. It washed these people away.”

Hassan and I are exact contemporaries: born in the same week in October 1988. His early 20s, though, were marked by climate-change induced price spikes. “You’d be paying $15 for a kilo of tomatoes: nobody could afford this. When wheat prices went up, that was when we really took to the streets.” I take a note: the 1788 famine, the wheat price spike, the storming of the Bastille the following year. A connecting line to our heating planet, to the project a producer friend is trying to get off the ground about Honduran fishermen who have formed gangs to battle over fishing spots. Hassan links phenomena such as these to the riots that interrupted his finals in May 2011.

“They weren’t letting women students take their finals, because some of them had been protesting against the regime,” he remembers. “So we all went out to back them up. You must understand, when everyone’s hungry, the stakes kind of get higher. There are too many of you for too few jobs. That’s how they divide you. But you can’t let your colleagues down. It might be you one day. The pro-government supporters gathered, too—they were paid by the regime; there were always so many more of them—so the campus was just full of two chanting factions. Then the secret police came, corralled us, led us up to our dormitories, saying we’d be expelled if we didn’t go. So we all pack into our dorms, and they cut off the electricity. Bam. Darkness. And all you hear is silence, a slamming noise, mad shouting, people sobbing or crying or yelling because they’re being beaten, the sound of fists and sticks on people’s bodies. As they got closer, I could hear them asking for IDs, home addresses. The beatings were louder when people said they were from Deraa or Homs, because they’re anti-regime cities. And we were freaking out, because my three roommates were Kurdish. They wanted us to get knives.” He shakes his head. “I mean, OK, so they were scared, but that is really fucking crazy. And then it was their turn to think I was crazy, because I opened the door for the police. I’m Alawite — I look like one of them. So the fact that I was so calm with them confused them — and also I was blocking the door, so they couldn’t see the Kurds. I remember three of them at the door, covered in blood, eyes twitching and jumpy — kind of…sniffling, too, right? Like they had taken a powder or something. Some kind of upper. I could see behind them — blood smears on the walls, blood on the stairs, like rain. So once the main guy — the boss or whatever, I don’t know — once he understood I was Alawite, he just wanted to know why we had no picture of Assad on the wall. Then he left.”

Through the window: steel on the skyline.

A sky made of glass.

Hassan’s a librarian, but he’s trying to get his Spanish up to speed so he can study urban planning. “Organizing books, organizing cities — it’s all data,” he smiles. “I just hope it doesn’t end the way my last job did. I had so many political arguments with my colleagues that they called the police on me. One day, these two policemen turned up, asking me if I wanted a coffee — that’s how they do it, super polite, super friendly. So every time you ask if I want some kind of hot beverage, I get worried.”

Following the police visit, Hassan’s cross-country scramble began, gathering and selling his things, dodging protests, crackdowns, and the growing number of military checkpoints set up to catch young Alawite men avoiding military service. He crossed into Turkey in early 2012, carrying $450, two jackets, and four books. Two of them were copies of 1984: one in English, one in Arabic. “I lived in that book,” he says. “There’s no other way to see it.”

That small library is battered after four years on the road. Hassan lists off the cities one by one. “Istanbul was a nightmare,” he laughs. “I couldn’t speak the language — so I was a terrible waiter. I ended up borrowing $100 from a friend to move to Beirut — a place I miss more than Damascus or Masyaf, actually. I had a good life there. I had an iPhone and everything,” he adds, wry for a moment.

“Rome was the only place I was depressed,” he says, sounding surprised. “It was limbo — poor, fear, an expired visa, a tiny apartment by the airport. I started working as a translator. In return, they promised to bring me here. But there were so many delays. I taught myself Italian to kill the time. Plus European racism put me off the idea of living there. To make friends, I had to say I was Israeli. Nobody wants to date a Syrian: they think we’re all in ISIS. But my friends and I had to drop the Israeli act. Someone tried to introduce us to actual Israelis in a bar. We dropped our drinks and ran.”

“What about the girlfriend you have now — if you stay, I mean — would that not be like building a home?”

“There is no home anymore,” Hassan says flatly, but with a smile. “Home’s not a place, or a language, or objects. When you move around, you discover how much you can leave behind. I have some tickets that hold memories, and the shipping receipt from when I sent my ex-girlfriend’s clothes to her in Denmark. These objects that I’ve kept mean more to me than my clothes,” he says, plucking the sleeve of his t-shirt, part of a wardrobe gifted to him by Mexico’s Syrian community.

“In Mexico, I can be anyone. I wear no label,” he goes on. “In Syria, my label says ‘Alawite’. But before that label existed, there were others: Ottoman, Roman, Persian… But here? I’m away from all that history, all that writing on people’s skin. I’m gone from all that. Maybe that freedom’s like home, in a way — just me out on my own.” He shrugs. “Yeah: maybe there is a home. It’s that serenity feeling, or something like it.”

3: Rain

“I love this,” says Luis, my flatmate, when he sees the news alert that says the traffic restrictions will be in place from now until the end of June: the usual beginning of the rainy season. “2016, right? And we’re still depending on the fucking rain god to sort us out like in 1300.” We’re irritable after a week of wearing beach clothes indoors. Luis mocks my tie-dye vests. I mock his shorts. A snail epidemic breaks out in one of his fishtanks because of a heat-induced algal bloom. I’m concerned that flushing them down the toilet will result in mutant snails fed on toxic sewage, slithering up our pipes for revenge. “Then don’t rinse food down the sink, maybe,” says Luis.

Earthquake weather, this is called, a reference to the jumpy, paranoid mental state that descends after days of airless swelter rather than to any direct link between quakes and hot days, since you’re more likely to remember an earthquake when the heat has you alternating between jumpiness and dizzy sleepiness.

Through the window: steel on the skyline. A sky made of glass. The buildings shine like external hard drives. I picture them shattered and strewn across a chemical-pink desert, imagine that last sunset as a swollen blood yolk. These surreal flashes are the last traces of migraine leaving my body. I crave rain to wash away the last residues, a big storm, the kind that cancels all space to a white roar. I wish O. would come over. I wish we could stand here and look out on the rain’s phosphor seethe, dreaming my sitting-room to a cave above a roaring sea. For a while that serenity feeling could be our home, or something like it.

--

All names have been changed.